To understand who the Holy Spirit is, we must first explore how the Bible uses the word spirit.

The Old Testament, originally written in Hebrew, uses the word ruach, which means breath, wind, or spirit. The New Testament, written in Greek, uses pneúma, which carries the same meanings.

When reading Scripture, we must determine the correct meaning of spirit, wind, or breath based on context. However, “spirit” remains the most common translation for ruach and pneúma. Whenever the adjective “holy” appears, it always refers to the Holy Spirit.

Mankind has a spirit also

Before we develop a clear understanding of “Who Is The Holy Spirit?” it’s helpful to understand that mankind has a spirit. Man’s spirit is defined as:

- The rational part of mankind that perceives and grasps divine and eternal things

- That part of mankind in which the Spirit of God exerts influence

- Said a different way, mankind’s spirit is “the highest and noblest part of man, which qualifies him to lay hold of incomprehensible, invisible, eternal things. It is the house where faith and God’s word are at home.” – Martin Luther

Overview of the Spirit of God

The Bible teaches that “All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine…” (2 Timothy 3:16). To know the Holy Spirit, we must rely on the Holy Bible, not personal experiences or encounters.

Scripture mentions the Spirit of God over 300 times—about 85 times in the Old Testament and 220 times in the New Testament. By studying these passages, we can develop a clear understanding of His role and nature.

As anyone who has studied the Holy Bible knows very well, the meaning of certain verses of scripture can be challenging to understand. Most verses have deep meaning that are not revealed unless you study that particular verse in depth. For example, Genesis 1:2 says “… And the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters.” This verse shows Holy Spirit working on the elements in preparation for a new creation. I know well that there is additional, deeper meaning but it is not wrong to identify the Holy Spirit as Creator here.

High level view of the Holy Spirit

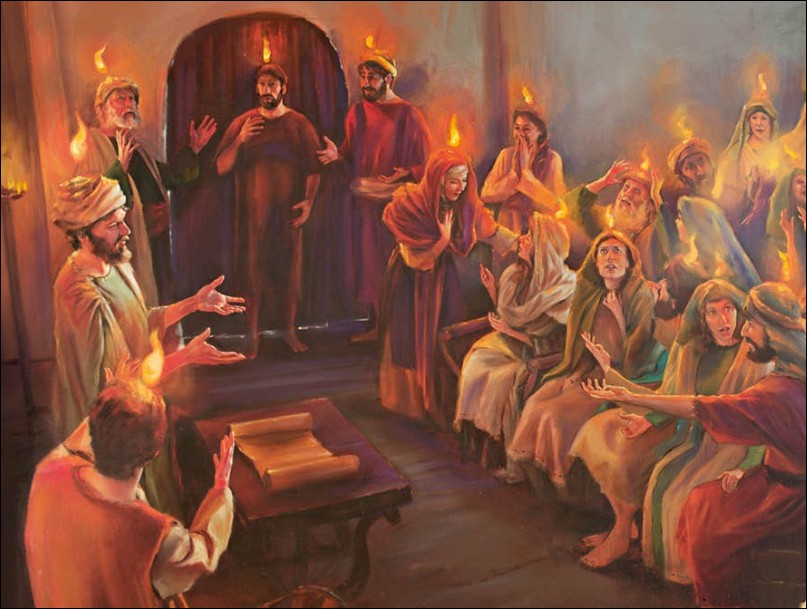

The expression “the Spirit of the Lord” denotes the person of God. What God does is done by the Spirit. The Holy Spirit is presented in Scripture as connecting humanity to God’s will. He is a gift-giver who sanctifies and renews us (Ezekiel 36:27, Titus 3:5), a mysterious companion we can’t fully control or understand (John 3:8), and a discerning guide who helps us separate good from evil (1 John 4:1-3). The Holy Spirit created and sustains life (Psalm 104:30). He sparks joy in our hearts (Luke 1:47) and prays for us when words fail (Romans 8:26). He’s a transformer too, changing lives by softening hearts (Ezekiel 11:19), calling people to specific tasks (Acts 13:2), and testifying to God’s truth (1 John 5:6). In all this, the Holy Spirit shapes us and the world according to His perfect plan.

Scripture also shows the Holy Spirit stands in contrast to deceptive spirits, highlighting His role in the battle between truth and lies. When He’s with us, He empowers and guides us; when He’s absent, we’re left struggling with confusion or corruption. The Holy Spirit even connects with our emotions—stirring joy, comforting sorrow, calming fear, and renewing our spirits. Across every situation He’s present with us, working in us, and leading us into God’s purpose with intention and care.

Related content: The Wonderful Jesus the Christ